What a strange thing to start off with! This semester I’m taking Advanced Linux Kernel Programming, a graduate level course at Virginia Tech.

Memory in the Kernel (whether it be Virtual Memory, Physical Memory, the slab layer, software caches, hardware caches) was one of the core takeaways of the course. Being as important and all-encompassing as it is, the concepts themselves are often explained in isolation and indeed, the implementation details span many chapters in reference books. What takes some reading, experimenting and understanding is the glue that binds these concepts together. I’m by no means an expert on the matter. However, this might actually work to our advantage as we won’t be assuming too much. I hope to provide my take/understanding on that glue here along with the tidbits of knowledge our professor gave to us throughout the course.

First things first – we will be talking about the Volatile Memory in a system, commonly known as RAM. It is byte addressable – which is different when compared to other Non-Volatile Memory storage (more on that in another post).

Virtual Memory

So, virtual memory – it gives the illusion of the system having more physical memory than we actually do. Here’s a diagram of that from Wikipedia:

Here are some things to always, always keep in mind as we proceed with our discussion of physical and virtual memory. The virtual memory footprint can be much larger than that of available physical RAM. Why? Virtual Memory is a way of “Reserving” RAM, creating a contract saying “Yes, this is the memory I need, I don’t care if it’s actually allocated right now, as long as I have it when I need it”. Thus, the kernel’s memory management system is free to lazily allocate physical memory to a given process only when it needs it. This is called demand paging. This setup essentially allows us to have much more Virtual Memory than there is Physical Memory. It also allows us to give multiple different processes the illusion that they have their own memory addresses starting at x and ending at y, while in reality, they are mapped to different physical memory locations.

The entire system’s Virtual Memory map would look similar to the diagram below. Note that higher linear addresses belong to the kernel while lower addresses belong to userspace. The “hole” is there due to the fact that while most modern processor architectures support 64-bit addresses and do indeed have 64-bit registers, memory access hardware only needs to support 48-bit addressing (providing us with up to 256 tebibytes of virtual memory). This is seen as more of a manufacturing cost awareness measure as indexing up to 16EB of memory is not needed at this point in time.

While we’re here, let’s just briefly go over the individual sections in kernel space memory shown below. From left to right,

- dirmap is the direct mapping of ALL physical addresses to the kernel’s virtual memory. This is where it’s important to keep in mind the fact that virtual memory is an illusion, and by having that mapped there, it’s merely saying that “If we access memory at that address, we can get the contents of the physical memory using a 1 to 1 mapping”. This is why the user | kernel boundary is guarded so tightly. Access to the kernel potentially means access to all currently mapped memory in the system. The direct mapping is also often used to access devices through memory-mapped-io. The ioremap kernel function provides an api to map these devices into usable virtual memory.

- vmalloc region is the virtual memory region where any calls to vmalloc will allocate physical memory (usually in the high-memory) to.

- virtual mem map where the page tables reside.

- kernel text .txt section for the kernel loaded.

- modules device drivers and other kernel modules loaded on demand.

In Linux, the Virtual Memory is tracked in a per-process structure called the mm and defined by struct mm_struct. You can find the definition here. Check the latest version of the kernel at the time of reading as the code does change (maybe not the core, but parts will change from version to version). We will go over the specifics of that data structure after touching the key concept that is the Virtual Memory Area(VMA).

The VMA is a logical concept and is represented by a kernel data structure called struct vm_area_struct. A single process has 1 mm_struct descriptor, that mm_struct descriptor will have many VMAs it has references to. Within a single process, each VMA maps to a non-overlapping contiguous chunk of memory containing the same permissions flags.

Try it yourself – on a linux system type the command below:

sudo cat /proc/1/maps

Now we’re ready to talk about the mm_struct or memory descriptor. Shown below is a minimized version of struct mm_struct, with many members not included for the brevity of this discussion.

struct mm_struct {

struct {

struct vm_area_struct *mmap;

struct rb_root mm_rb;

unsigned long mmap_base;

unsigned long task_size;

unsigned long highest_vm_end;

pgd_t * pgd;

int map_count;

spinlock_t page_table_lock;

struct rw_semaphore mmap_sem;

struct list_head mmlist;

unsigned long total_vm;

} __randomize_layout;

unsigned long cpu_bitmap[];

};mmap and mm_rb are essentially different data structure linkages for the same VMAs owned by a particular process. mmap is a linked list of VMAs usually used to clear them all, and mm_rb is a red-black tree of VMAs, used for fast lookups. pgd holds the physical address of the Page Global Directory (PGD), and is also written into the CR3 register so the memory management unit can help us walk the table to find our Virtual Address to Physical Address mapping – something we will go over briefly in the next section.

Hardware

None of this would work fast without the help of hardware. Like many other things, having extra help from the hardware is a tried and tested way to increase throughput. Similar to how graphics rendering or highly parallelized workloads might be delegated off to the GPU or FPGA’s, memory operations are delegated to the Memory Management Unit(MMU)!

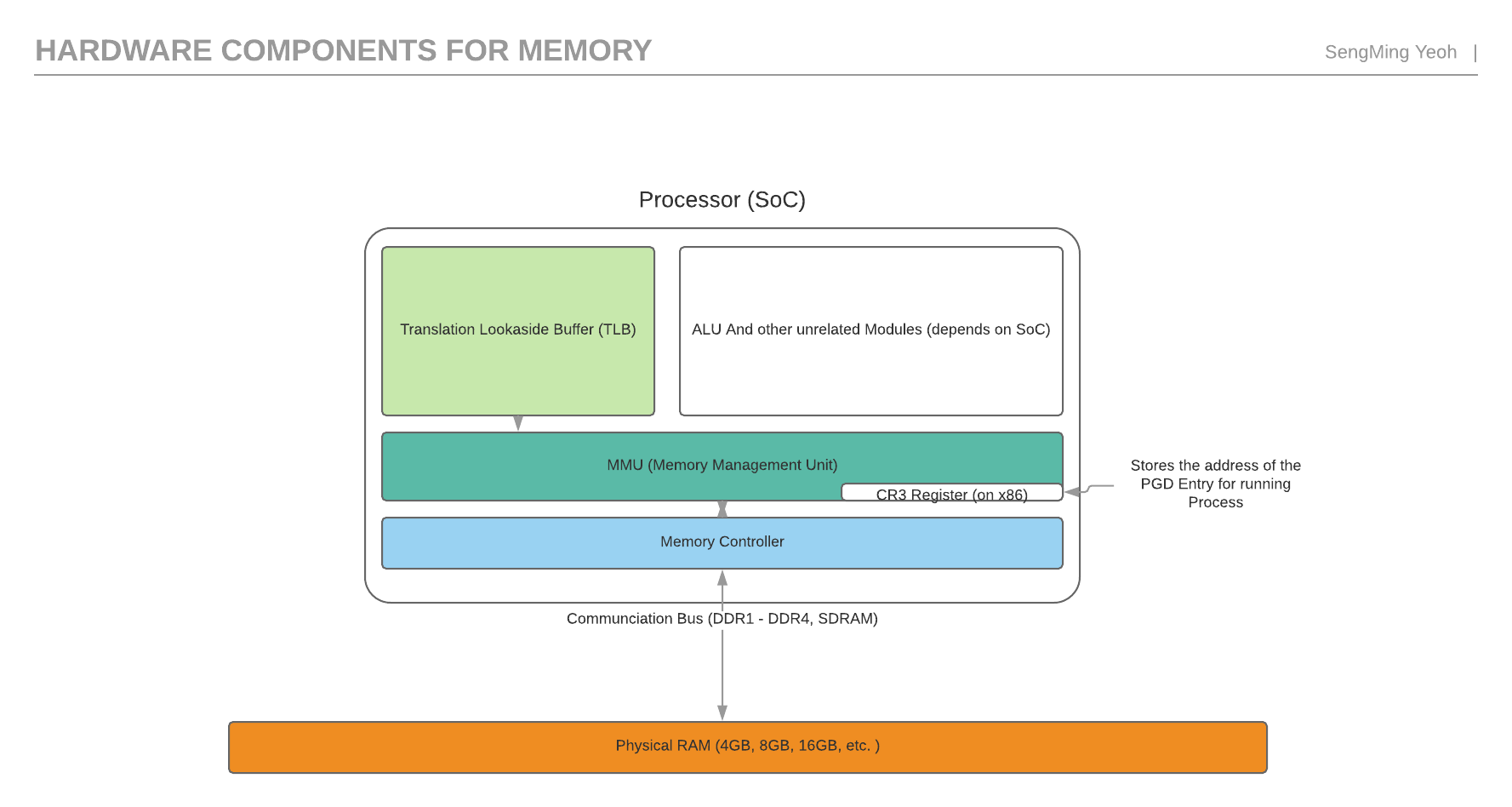

A physical diagram of what the MMU and its relationship with memory might look like is shown here:

Let’s break it down. The SoC(System on Chip) has a memory controller which it uses to interface with physical RAM via a communication bus. This then interfaces with the MMU . For the Intel x86_64 architecture, the CR3 Register will simply hold the address of the Page Global Directory entry for a given process.

One important thing to remember is the PGD entry is a per-process structure. We will cover the PGD -> PUD -> PMD -> PTE page frame mapping in the next section. For the sake of this discussion, it is enough to know that the MMU takes a Virtual Address and returns a Physical Address if it’s found. You might be wondering what happens to it when a context switch occurs since it’s a per-process structure! After all, this is the hardware itself now and there is no virtualization at this level. At each context switch, the CR3 register is updated to point to the new PGD entry for that given process (represented by a struct task_struct).

The Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB) is part of the hardware and performs the role of caching virtual to physical address translations. Walking the page tables can be an expensive process and while relatively small the TLB is integral to reducing the time it takes to perform an address translation.

The MMU plays these three crucial roles with respect to our discussion:

- Does a TLB Check to see if the PTE is currently cached.

- Performs page table walks to find Virtual Address to Physical Address mappings.

- Traps into the kernel to handle the page fault if the page table and TLB do not contain a PTE for a given Virtual Address. (Linux in general is really lazy and will grow the Virtual Address space first and wait for pagefaults before mapping in the Physical Memory)

Paging in Linux

Now that we’re aware of the virtual memory to physical memory relationship within processes is structured in the kernel and the hardware’s role in this let’s talk about how the kernel and the hardware maintain this accounting – via Paging. When learning about paging, one thing that completely threw me off was the fact that it has very little to do with the page cache, another concept in Linux and how the non-volatile memory is managed. While they do indirectly interact with each other through swapping, we will cover that in another part.

Pages or page frames are physically contiguous blocks of volatile memory. In Linux systems, given a linear address they are arranged as such, forming a radix tree with a key that is the virtual address, and value being the physical address. Again, each process will have its own memory descriptor, and thus, its own tree. The actual layout of each page table entry(PTE) is architecture specific, but usually there is a bit denoting if that physical page is currently in use by another process to avoid overlapping physical pages:

Each Level of the tree is based on a key index at an offset from the linear virtual address, as seen here:

Since these types are architecture specific, as expected, you can find them in architecture specific directories within the kernel source: x86 is here. For example, pud_t, pmd_t and pgd_t.

Connecting These Concepts Together

Finally, a quick note on how these concepts tie together in a basic memory request.

- A process attempts to access a memory address in a particular VMA.

- The MMU checks its TLB to see if it has that entry cached.

- If the entry isn’t cached, the processor will do a page-table walk using the pgd stored in its cr3(on x86) register to find the particular page frame.

- The page frame offset is found and the memory is retrieved.

Here’s the big question – we know that VMAs are virtual contracts, so they can be grown and decreased at will by the kernel, without actually mapping to physical memory! What happens if in step 4, the page frame is NOT found in physical memory? This is where page faults and demand paging comes in. Think about it. We’ll cover that in Part 2.